Satipatthana er en svært sentral lære i buddhismen, og den peker på hvordan oppmerksomhet etableres eller anvendes for å oppnå visdom og frihet. Denne undervisningen ble gitt en helg i Oslo, og diskuterer en del myter og så presenteres oppmerksomheten i henhold til tidlig buddhisme. Dette er en grundig teoretisk innføring, som gir et fint oversikt for egen praksis.

Podcast episoder

Spill av episodene i denne nettleseren, eller bruk en podcast app:

Hva betyr egentlig ‘riktig oppmerksomhet’ i buddhismen? Ajahn Brahmali forklarer begrepet ‘samma sati’ og hvordan det er knyttet til meditasjon og den åttedelte vei. Vi får innsikt i hvorfor mindfulness ikke kan forstås isolert, men må ses i en større helhet.

Denne undervisningen ble gitt i Oslo 2025, og notatene til undervisningen finnes på denne nettsiden:

https://dnbf.org/2025/07/riktig-oppmerksomhet/

– – –

Anbefal gjerne denne podcasten til dine venner!

Tilbakemelding

Hvis du har tilbakemeldinger eller spørsmål om denne podcasten, send en e-post til: post@dnbf.org

Donasjon

Det frivillige foreningen DNBF har sammen med instruktøren produsert og distribuert denne podcasten gratis og uten reklame, men vi er avhengig av økonomisk støtte gjennom engangsgaver eller månedlige beskytterdonasjoner for vår drift og utvikling:

DNBF-donasjon – https://dnbf.org/donasjon/

DNBF-patron – https://dnbf.org/patron/

Nyhetsbrev

Abonner på vårt nyhetsbrev for å motta informasjon om våre aktiviteter:

https://dnbf.org/nyhetsbrev/

Medlemskap

Du er velkommen som medlem, og vi har mye å tilby av aktiviteter:

https://dnbf.org/medlemskap/

Problemer

Hvis du har et problem med denne podcasten, send en e-post til: post@dnbf.org

Innhold

- Right Mindfulness

- Myth 1 – The Satipaṭṭhāna Suttas are the most important suttas

- Myth 2 – Satipaṭṭhāna can be fully understood through the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta

- Myth 3 – Satipaṭṭhāna can be done without morality

- Myth 4 – Satipaṭṭhāna is equivalent to vipassanā

- Myth 5 – Satipaṭṭhāna is choiceless awareness of the present moment

- Myth 6 – Satipaṭṭhāna is to be practiced without joy or bliss

- Right Mindfulness In Early Buddhism

- Myths/misconceptions

- (1) Satipaṭṭhāna develops mindfulness

- (2) You are either mindful or you are not

- (3) Satipaṭṭhāna is “the one and only way”

- (4) Satipaṭṭhāna is all about direct observation: anupassanā/vipassanā

- (5) Breath meditation belongs to body contemplation

- (6) Satipaṭṭhāna is to be practiced in everyday life

- (7) Satipaṭṭhāna includes watching pain

- Summary of myths/misconceptions

- Overview of the Pali Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta

- Contemplation of body

- Contemplation of feelings

- Contemplation of mind

- Contemplation of dhammas

- Summary Satipaṭṭhāna

- Summary of entire course

Right Mindfulness

Right mindfulness (sammāsati) is about meditation.

What we are trying to achieve:

- To understand the place of meditation on the path

- To understand how meditation works

- To understand how meditation is done

Sequence of the N8P:

- Right view (sammādiṭṭhi) >

- Right aim (sammāsaṅkappa) >

- Right speech (sammāvācā) >

- Right action (sammākammanta) >

- Right livelihood (sammāājīva) >

- Right effort (sammāvāyāma) >

- Right meditation (sammāsati) >

- Right stillness (sammāsamādhi)

Definition of sammāsati:

“It’s when you meditate by observing an aspect of the body/feeling/mind/qualities—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world.” (SN 45.8) (= satipaṭṭhāna).

- Sammāsati = satipaṭṭhāna

- Right mindfulness = the applications of mindfulness

The breadth of texts on satipaṭṭhāna:

- Satipaṭṭhāna Suttas (MN 10 + DN 22)

- Satipaṭṭhāna Saṃyutta (SN 47)

- Various other suttas

- Satipaṭṭhāna in the Abhidhamma

- Satipaṭṭhāna outside the Pali tradition

Satipaṭṭhāna as refuge (SN 47.9):

“So Ānanda, be your own island, your own refuge, with no other refuge. Let the teaching be your island and your refuge, with no other refuge. And how does one do this?”

“It’s when you meditate by observing an aspect of the body … feelings … mind … qualities—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world.”

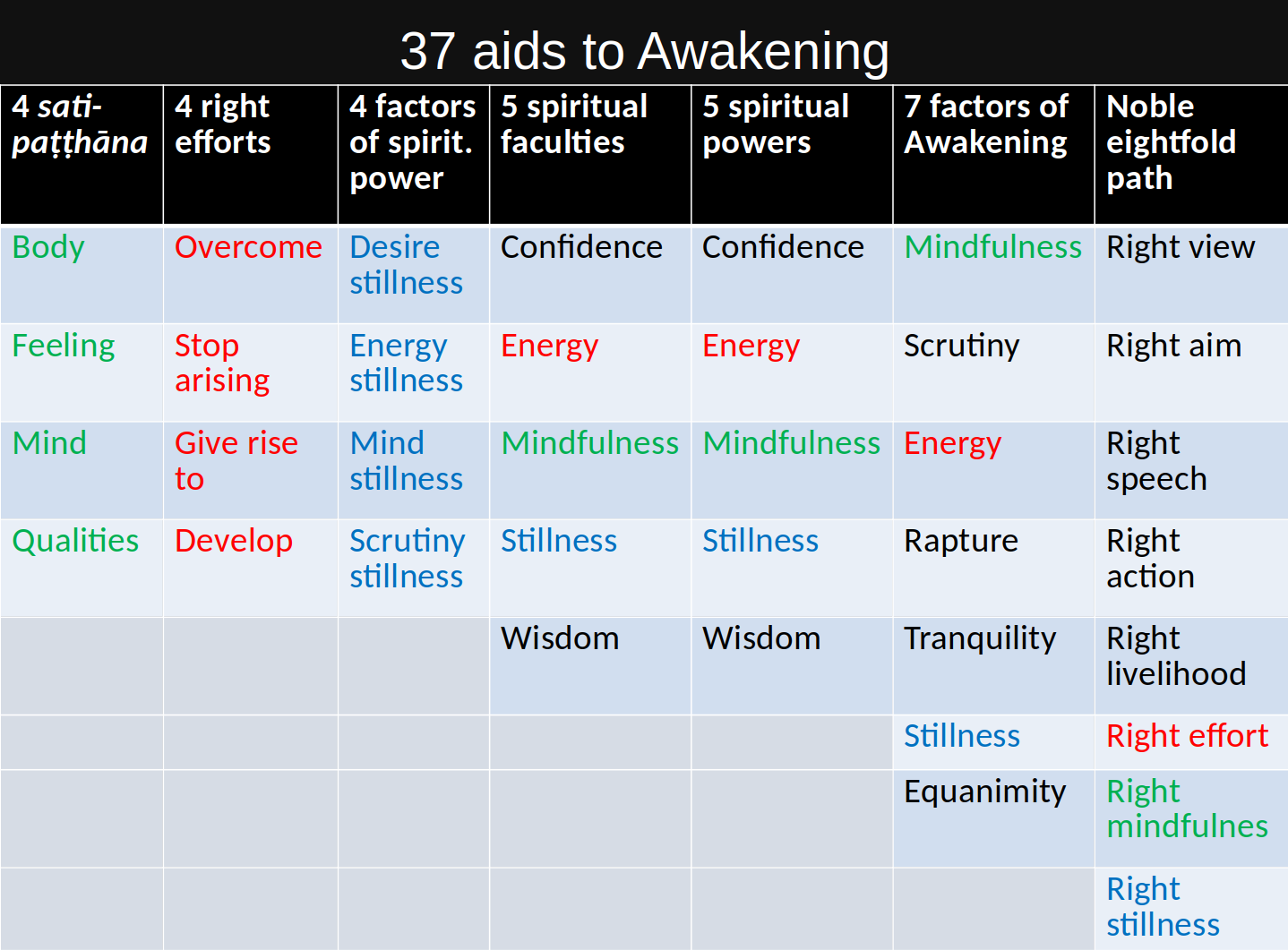

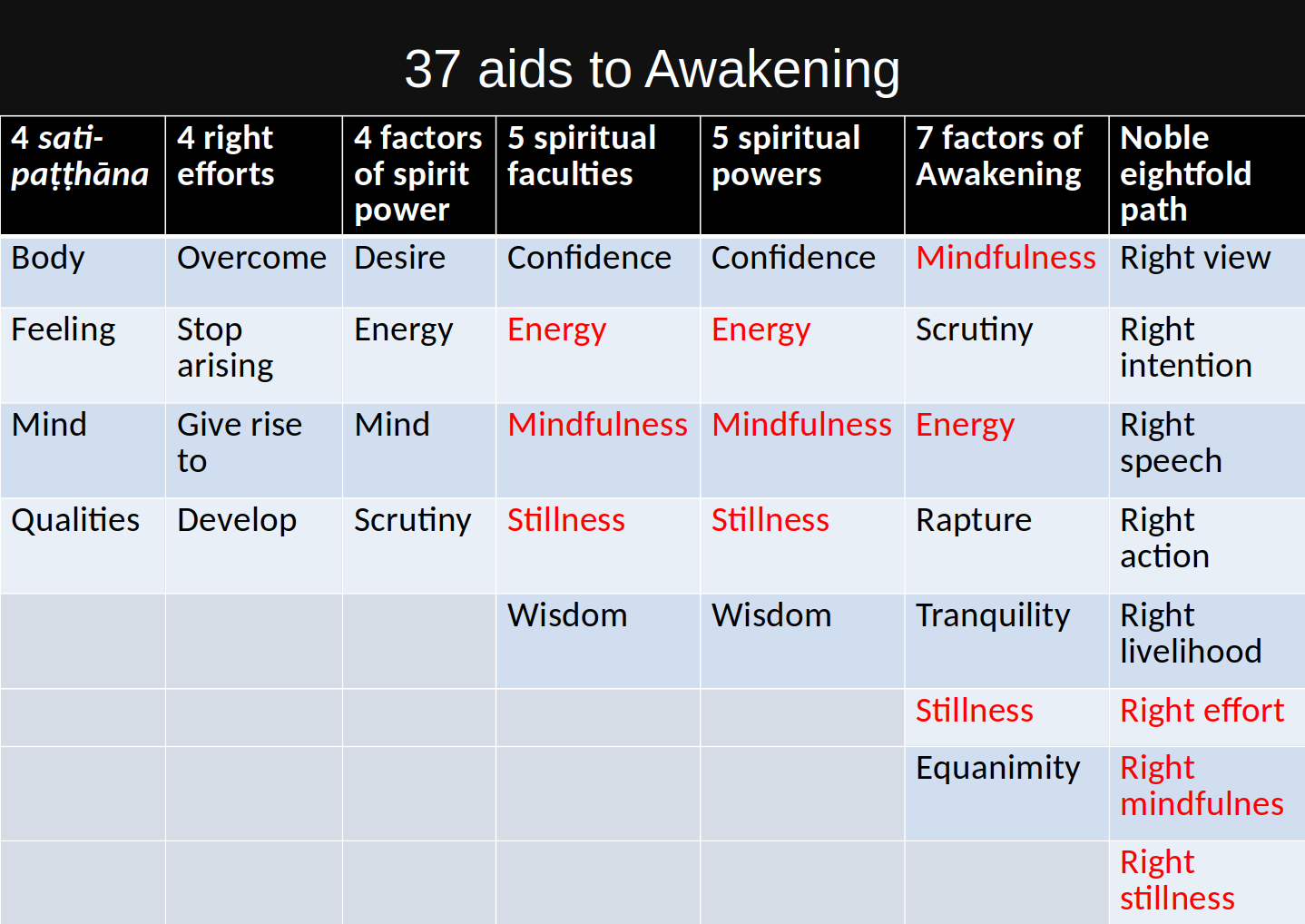

Aids to Awakening (37 bodhipakkhiyadhamma):

- 4 applications of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna)

- 4 right efforts (sammāpadhāna)

- 4 bases of spiritual power (iddhipada)

- 5 spiritual faculties (indriya)

- 5 spiritual powers (bala)

- 7 factors of awakening (sambojjhaṅga)

- Noble eightfold path (ariya aṭṭhaṇgika magga)

Basic principles of Dhamma:

“These four basic principles are primordial, long-standing, traditional, and ancient. They are uncorrupted, as they have been since the beginning. They’re not being corrupted now nor will they be. Sensible ascetics and brahmins don’t look down on them. What four?

- Contentment

- Good will

- Right mindfulness

- Right stillness (AN 4.29)

The meaning of satipaṭṭhāna:

- Satipaṭṭhāna = sati + upaṭṭhāna

- Upaṭṭhāna is: Standing near, establishing, application, focusing

The meaning of satipaṭṭhāna:

- Foundations of mindfulness

- Establishings of mindfulness

- Applications of mindfulness

- Focuses of mindfulness

The meaning of sati:

Memory:

“Furthermore, a person is mindful (satimā). They have utmost mindfulness (sati) and alertness (nepakka), and can remember (saritā) and recall (anussaritā) what was said and done long ago.” (AN10.17)

Awareness:

“When they have ill will in them, they understand: ‘I have ill will in me.’ When they don’t have ill will in them, they understand: ‘I don’t have ill will in me.’” (MN10)

Sati is memory + awareness:

- Good memory requires strong awareness, both in the act and in recalling the act.

- Awareness includes the memory of what we are supposed to be doing.

Definition of satipaṭṭhāna:

- The application of awareness and memory (= mindfulness) to four different areas.

- The word “mindfulness” is suitably vague to cover both these areas.

Degrees of mindfulness:

- Satipaṭṭhāna is the most prominent kind of mindfulness in the suttas.

- This is where mindfulness comes into its own, becoming fully established.

Characteristics of sati in satipaṭṭhāna. Free of ill will and desire:

- Present

- Stable

- Clear

- Peaceful

Place of satipaṭṭhāna on the path:

- Right effort >

- Right mindfulness >

- Right stillness

Place of satipaṭṭhāna on the path:

- Restrain the sense faculties so that desire and aversion (abhijjhā-domanassā) do not overwhelm you.

- After getting rid of desire and aversion (abhijjhādomanassa), you practice meditation (satipaṭṭhāna).

- After giving up the five hindrances, you attain jhāna.

Right effort leading to satipaṭṭhāna:

“When your morality (sīla) is well purified and your view is correct, you should develop the four applications of mindfulness three ways, depending on and grounded on morality (sīla).” (SN 47.3)

Satipaṭṭhāna leading to samādhi:

“The Buddha has described the four applications of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna) for achieving what is skilful (kusala). … When you practice the satipaṭṭhānas, you become rightly stilled (sammā samādhiyati) and rightly serene.” (DN 18)

The purpose of satipaṭṭhāna:

- Removes refined defilements

- Gives rise to joy

- Stills the mind

- Anything else?

Satipaṭṭhāna removes refined defilements:

“In the same way, a noble disciple has these four applications of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna) as tethers for the mind so as to subdue behaviors of the lay life, memories and thoughts of the lay life, the stress, weariness, and fever of the lay life, to end the cycle of suffering and to realize extinguishment.” (MN 125)

Satipaṭṭhāna removes defilements:

“An astute, competent, skillful monastic meditates by observing an aspect of the body—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world. As they meditate observing an aspect of the body … their corruptions (upakkilesa) are given up.” (SN 47.8)

Satipaṭṭhāna gives rise to joy:

- Joy and bliss are mentioned a number of places in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta. (MN 10)

- Mindfulness of breathing (ānāpānasati) includes joy and bliss. (MN 118)

“You meditate observing an aspect of the body—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world.’

When this stillness (samādhi) is well developed and cultivated in this way, you should develop it … with joy (pīti) … You should develop it with bliss (sukha).” (AN 8.63)

Satipaṭṭhāna stills the mind:

“An astute, competent, skillful monastic meditates by observing an aspect of the body—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world. As they meditate observing an aspect of the body their mind enters samādhi.” (SN 47.8)

“Right effort, right mindfulness, and right stillness: these things are included in the category of stillness (samādhi).” (MN 44)

“The four applications of mindfulness are the foundations of stillness (samādhi).” (MN 44)

The vital conditions and supports of noble samādhi are: right view, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, and right mindfulness. (MN 117)

Anything else?

“The four satipaṭṭhānas is the path to purify sentient beings, to get past sorrow and crying, to make an end of pain and sadness, to end the cycle of suffering, and to realize extinguishment.” (MN 10)

Tenfold path (AN 10.103):

- Right view >

- right purpose >

- right speech >

- right action >

- right livelihood >

- right effort >

- right mindfulness >

- right stillness >

- right knowledge (sammāñāṇa) >

- right freedom (sammāvimutti)

Two “levels” of satipaṭṭhāna:

- Satipaṭṭhāna >

- samādhi >

- satipaṭṭhāna (= sammāñāṇa) >

- sammāvimutti

Myth 1 – The Satipaṭṭhāna Suttas are the most important suttas

“[The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta] is by all Buddhists rightly considered the most important part of the whole Sutta-Piṭaka and the quintessence of the whole meditation practice.” Bhikkhu Nyanatiloka

“And what are those things I have taught from my direct knowledge? They are: the four kinds of mindfulness meditation, the four right efforts, the four bases of psychic power, the five faculties, the five powers, the seven awakening factors, and the noble eightfold path.

“Having carefully memorized them, you should cultivate, develop, and make much of them so that this spiritual practice may last for a long time. That will be for the welfare and happiness of the people, for the benefit, welfare, and happiness of gods and humans.” DN 16

Myth 2 – Satipaṭṭhāna can be fully understood through the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta

The opposite is true: Satipaṭṭhāna will be mis-understood if one only considers the Satipaṭṭhāna Suttas. Satipaṭṭhāna can only be understood by considering all the EBTs.

- Satipaṭṭhāna Suttas (MN 10 + DN 22)

- Satipaṭṭhāna Saṃyutta (SN 47)

- Various other suttas

- Satipaṭṭhāna in the Abhidhamma

- Satipaṭṭhāna outside the Pali tradition

Myth 3 – Satipaṭṭhāna can be done without morality

Mindful fishing? (photo: Richard R)

“When your morality (sīla) is well purified and your view is correct, you should develop the four applications of mindfulness in three ways, depending on and grounded on morality (sīla).” (SN 47.3)

Morality is very broad:

- Positive and negative morality (sīla)

- Sense restraint (indriya saṃvara)

- Clear awareness (sati-sampajañña)

Correct view:

- Seeing the limits of the material world (anicca)

- Understanding how people are conditioned (anattā)

Myth 4 – Satipaṭṭhāna is equivalent to vipassanā

“Satipaṭṭhāna is vipassanā. Vipassanā is satipaṭṭhāna.” (Goenka)

Satipaṭṭhāna (= sammāsati) > sammāsamādhi

There is no link between satipaṭṭhāna and vipassanā in the suttas. They are never used together. Satipaṭṭhāna is the practice. Samatha and vipassanā are the result.

Myth 5 – Satipaṭṭhāna is choiceless awareness of the present moment

When you decide on the meditation subject there is choice. When you attend to the subject there is choice. When you contemplate there is choice.

The idea of a “present moment” is from the Abhidhamma. In the suttas there is only the present, paccuppanna. There is change from sense to sense, but not “momentariness”:

“These is arising, vanishing, and change while persisting.” (SN 22.37)

Myth 6 – Satipaṭṭhāna is to be practiced without joy or bliss

“When they feel a material pleasant feeling (sāmisa sukha), they know: ‘I feel a material pleasant feeling.’

When they feel a spiritual pleasant feeling (nirāmisa sukha), they know: ‘I feel a spiritual pleasant feeling.’” (MN 10)“They know expansive mind as ‘expansive mind’ (mahaggata citta) … They know mind that is supreme as ‘mind that is supreme’ (anuttara citta) … They know stilled mind as ‘stilled mind’ (samāhita citta) … They know freed mind as ‘freed mind’ (vimutta citta) …” (MN 10)

“When they have the awakening factor of energy … rapture (pīti) … tranquillity (passaddhi) … stillness (samādhi) … equanimity (upekhā) in them, they understand: ‘I have the awakening factor of energy … rapture … tranquillity … stillness … equanimity in me.’” (MN 10)

Right Mindfulness In Early Buddhism

Satipaṭṭhāna summary statement:

“It’s when a monastic meditates by observing an aspect of the body—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world.”

Idha, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāye kāyānupassī viharati ātāpī sampajāno satimā, vineyya loke abhijjhādomanassaṁ.

Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta context: refrain

- Observing the body:

- Mindfulness of breath + refrain

- Four postures + refrain

- Full awareness + refrain

- 31 parts of body + refrain

- 4 elements + refrain

- Cemetery contemplation + refrain

+ same for observing feelings, mind, and mental qualities.

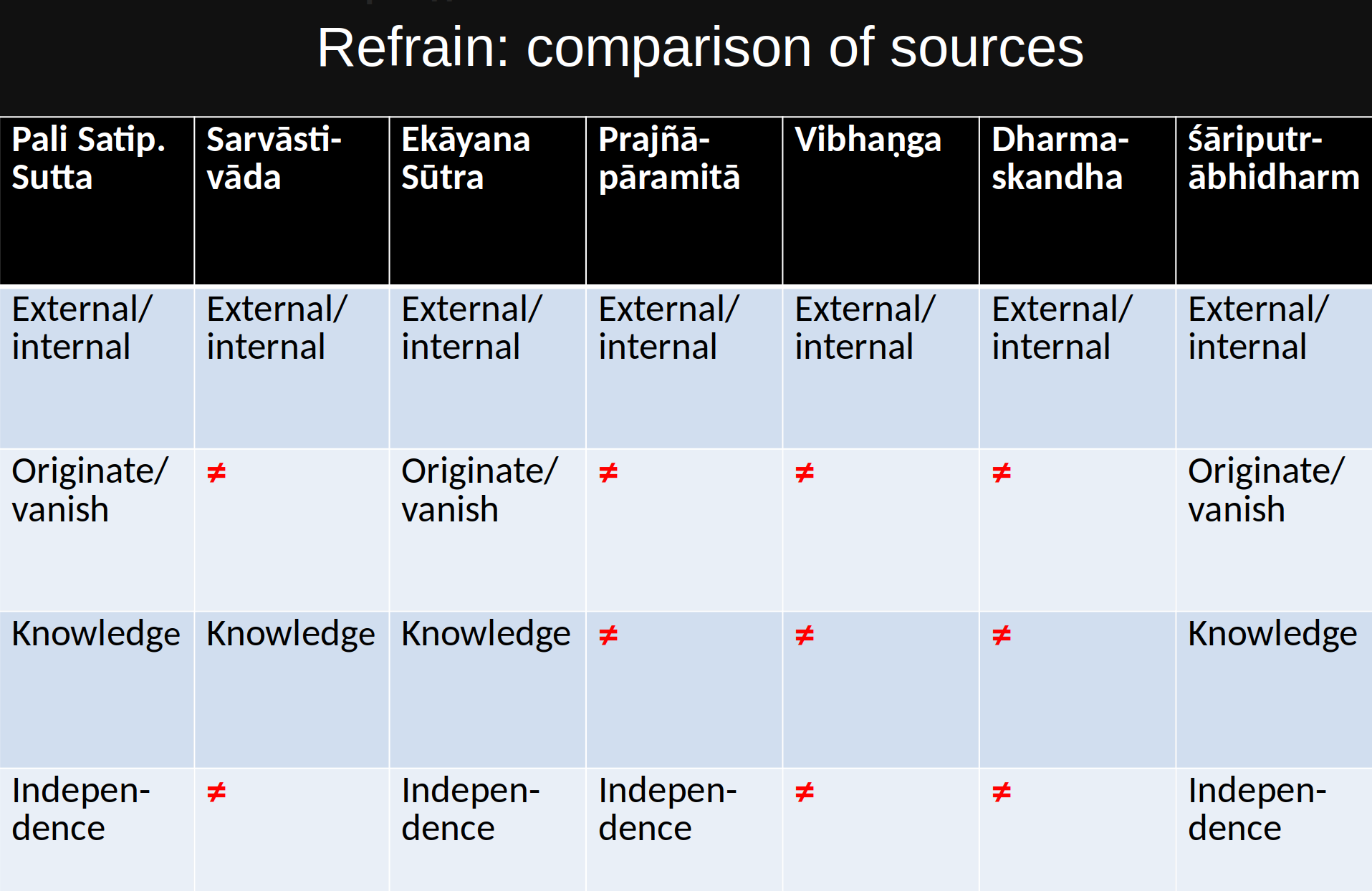

“And so they meditate observing an aspect of the body internally, externally, and both internally and externally. (1) They meditate observing the body as liable to originate, as liable to vanish, and as liable to both originate and vanish. (2) Or mindfulness is established that the body exists, to the extent necessary for knowledge and mindfulness. (3) They meditate independent, not grasping at anything in the world.” (4)

Refrain part 1:

“And so they meditate observing an aspect of the body internally (ajjhatta), externally (bahiddhā), and both internally and externally.” (MN 10)

“As they meditate observing an aspect of the body internally, they become rightly stilled (sammā samādhiyati), rightly serene.

They then give rise to knowledge and vision of other people’s bodies externally.” (DN 18)

Refrain part 2:

“They meditate observing the body as liable to originate, as liable to vanish, and as liable to both originate and vanish.”

“Whatever is liable to originate is liable to cease.”

Yaṁ kiñci samudayadhammaṁ sabbaṁ taṁ nirodhadhammanti. (e.g. AN 8.21)

“… an educated noble disciple truly understands form … feeling … perception … the will … consciousness, which is liable to originate … liable to vanish … liable to originate and vanish, as liable to originate and vanish.” (SN 22.136)

Refrain part 3 and 4:

“Or mindfulness is established that the body exists, to the extent necessary for knowledge and mindfulness.

They meditate independent, not grasping at anything in the world.”

“When they meditate observing impermanence, dispassion, cessation, and letting go in those feelings, they don’t grasp at anything in the world. Not grasping, they’re not anxious. Not being anxious, they personally become extinguished.” (MN 37)

| Pali Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta | Original Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta |

|---|---|

| Internal/external | = |

| Originate/vanish | ≠ |

| Knowledge | Perhaps |

| Independence | Perhaps |

“And so they meditate observing an aspect of the body/feelings/mind/mental phenomena internally, externally, and both internally and externally. (1)

They meditate observing the body (etc.) as liable to originate, as liable to vanish, and as liable to both originate and vanish. (2)

Or mindfulness is established that the body (etc.) exists, to the extent necessary for knowledge and mindfulness. (3)

They meditate independent, not grasping at anything in the world.” (4)

Summary

The refrain passage of the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta agrees with the overwhelming evidence from the suttas that satipaṭṭhāna is chiefly concerned with achieving samādhi.

Myths/misconceptions

- Satipaṭṭhāna develops mindfulness

- You are either mindful or you are not

- Satipaṭṭhāna is “the one and only way”

- Satipaṭṭhāna is all about direct observation: anupassanā/vipassanā

- Breath meditation belongs to body contemplation

- Satipaṭṭhāna is to be practiced in everyday life

- Satipaṭṭhāna includes watching pain.

(1) Satipaṭṭhāna develops mindfulness

“It’s when a monastic meditates by observing an aspect of the body—keen, aware, and mindful, rid of desire and aversion for the world.”

Idha, bhikkhave, bhikkhu kāye kāyānupassī viharati ātāpī sampajāno satimā, vineyya loke abhijjhādomanassaṁ.

(2) You are either mindful or you are not

If this were so, you could gain full insight once sati is established. Sati comes in different degrees, depending on the strength of one’s samādhi and wisdom. (SN 48.12) Mindfulness needs the power and brightness of samādhi to gain deep insight.

(3) Satipaṭṭhāna is “the one and only way”

After a study of pre-Buddhist Brahmanical texts, Bhante Sujato arrives at the following translation for ekāyano maggo:

“This is the path to convergence” (“This is the path going to one”)

Convergence here refers to convergence of mind, that is, samādhi, “stillness”

Ekāyano maggo > (satipaṭṭhāna is) the path to samādhi.

(4) Satipaṭṭhāna is all about direct observation: anupassanā/vipassanā

(a) Imagination: contemplating the 31 parts of the body.

(b) Inferential knowledge: there are two kinds of knowledge, experiential (dhamma ñāṇa ) and inferential (anvaya ñāṇa).

Inferential knowledge is about the future and the past, especially future and past lives, and other people.

(c) Retrospective insight:

“ … a monastic … enters and remains in the first absorption …

They contemplate the phenomena there—form, feeling, perception, choices, and consciousness—as impermanent, as suffering … as not-self.” (MN 64)

= Ānāpānasati Sutta

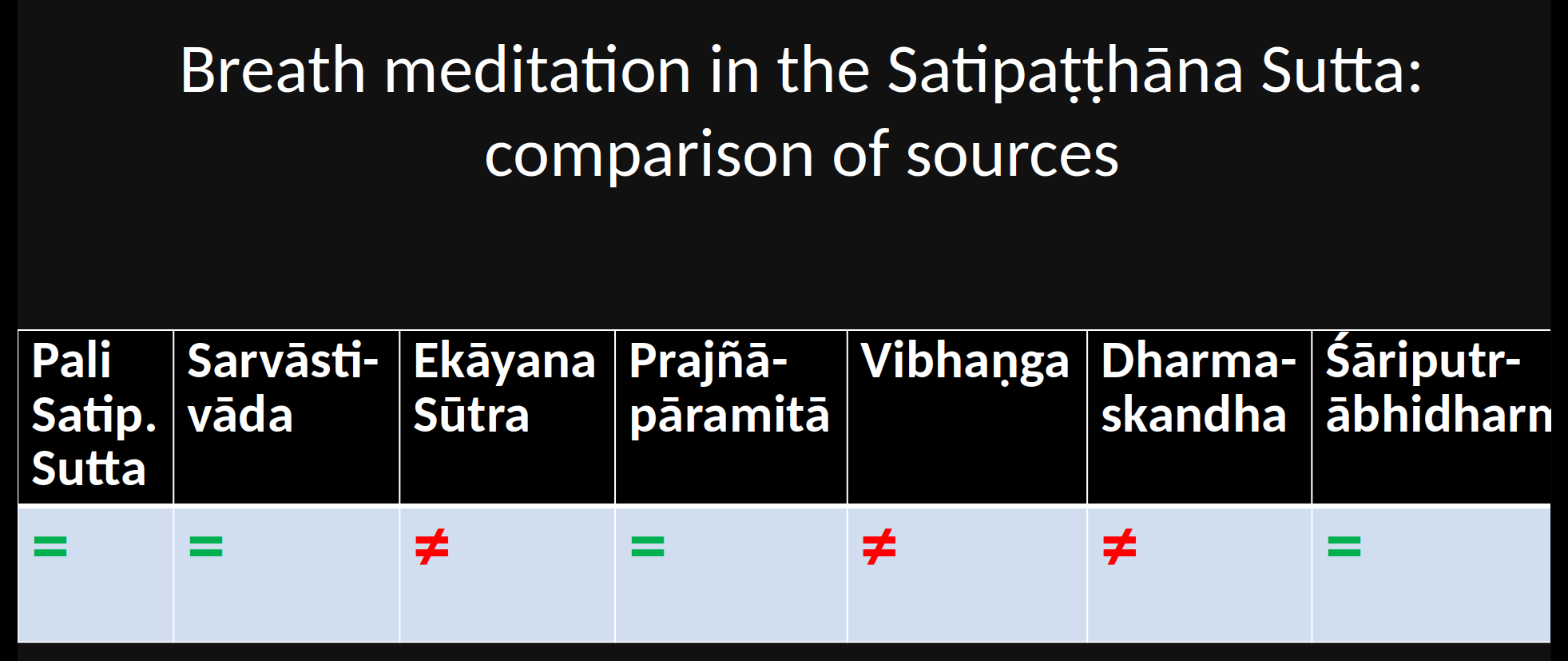

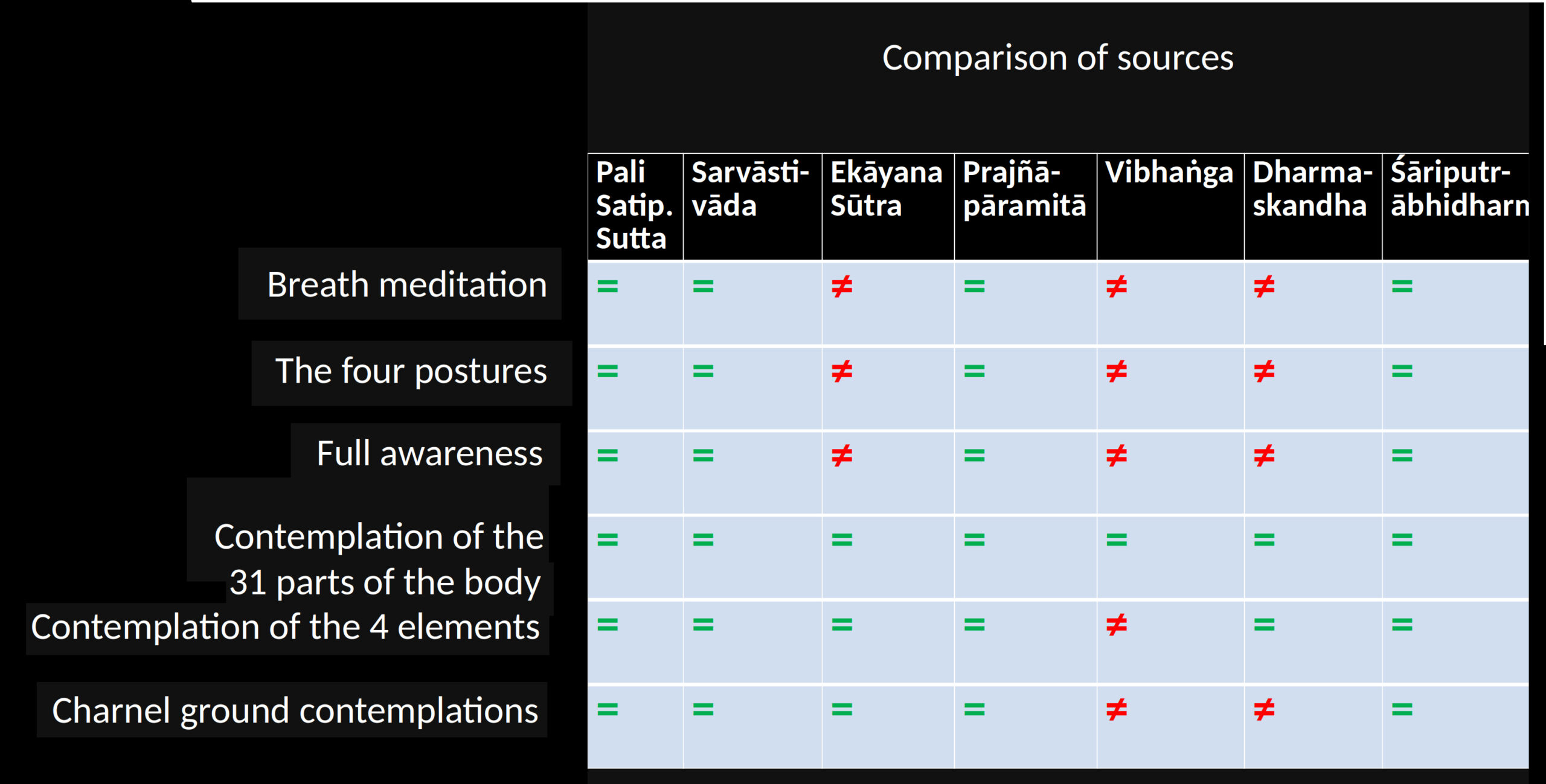

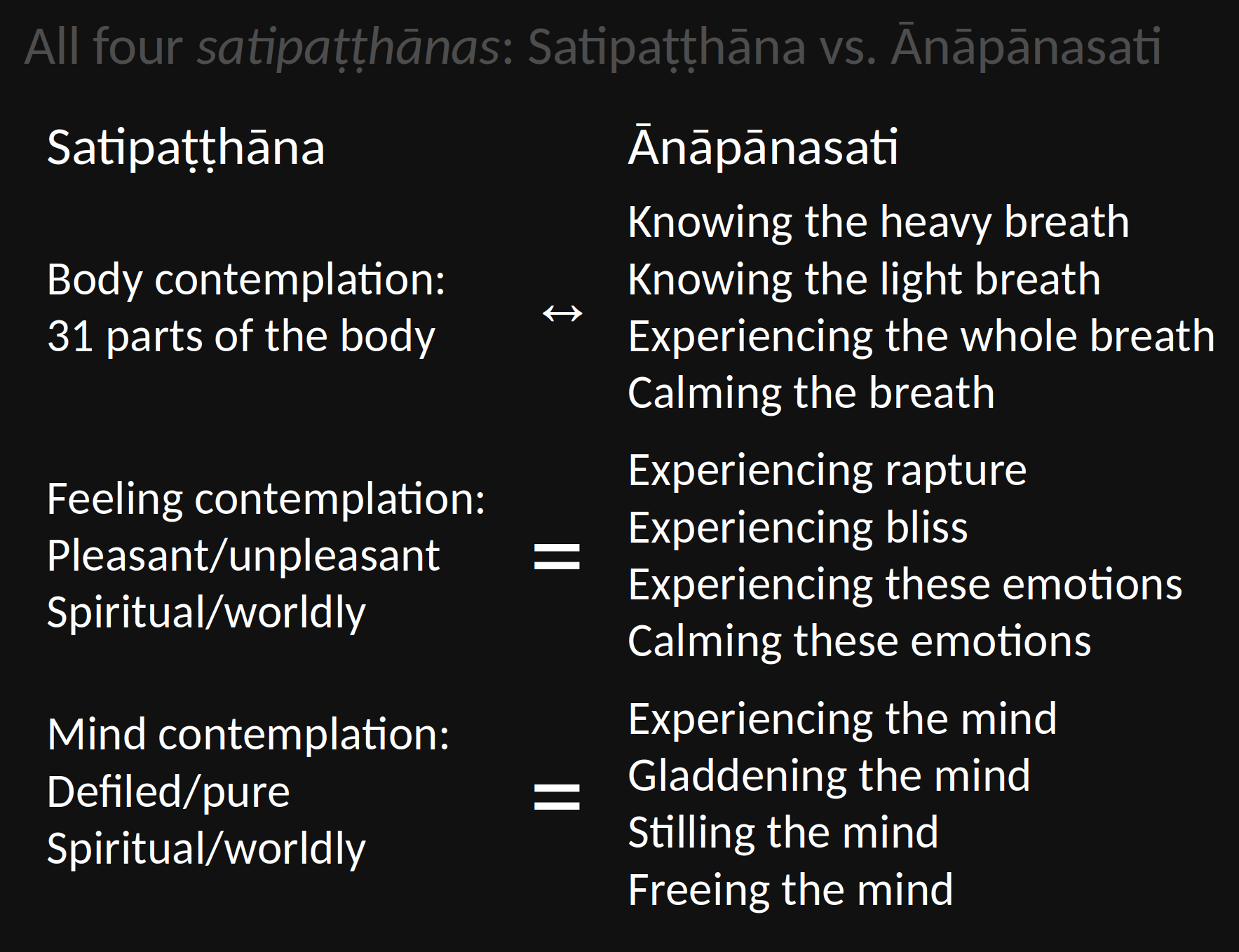

(5) Breath meditation belongs to body contemplation

In Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta breath meditation is only found with body contemplation:

“And how does a monastic meditate observing an aspect of the body? It’s when a mendicant … sits down cross-legged … Just mindful, they breathe in. Mindful, they breathe out.” (MN 10)

But in the Ānāpānasati Sutta breath meditation covers all four satipaṭṭhānas:

“Mindfulness of breathing, when developed and cultivated, fulfills the four satipaṭṭhānas …” (MN 118)

We can conclude that breath meditation does not belong under body contemplation in the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta. How? Because breath meditation belongs to all four satipaṭṭhānas.

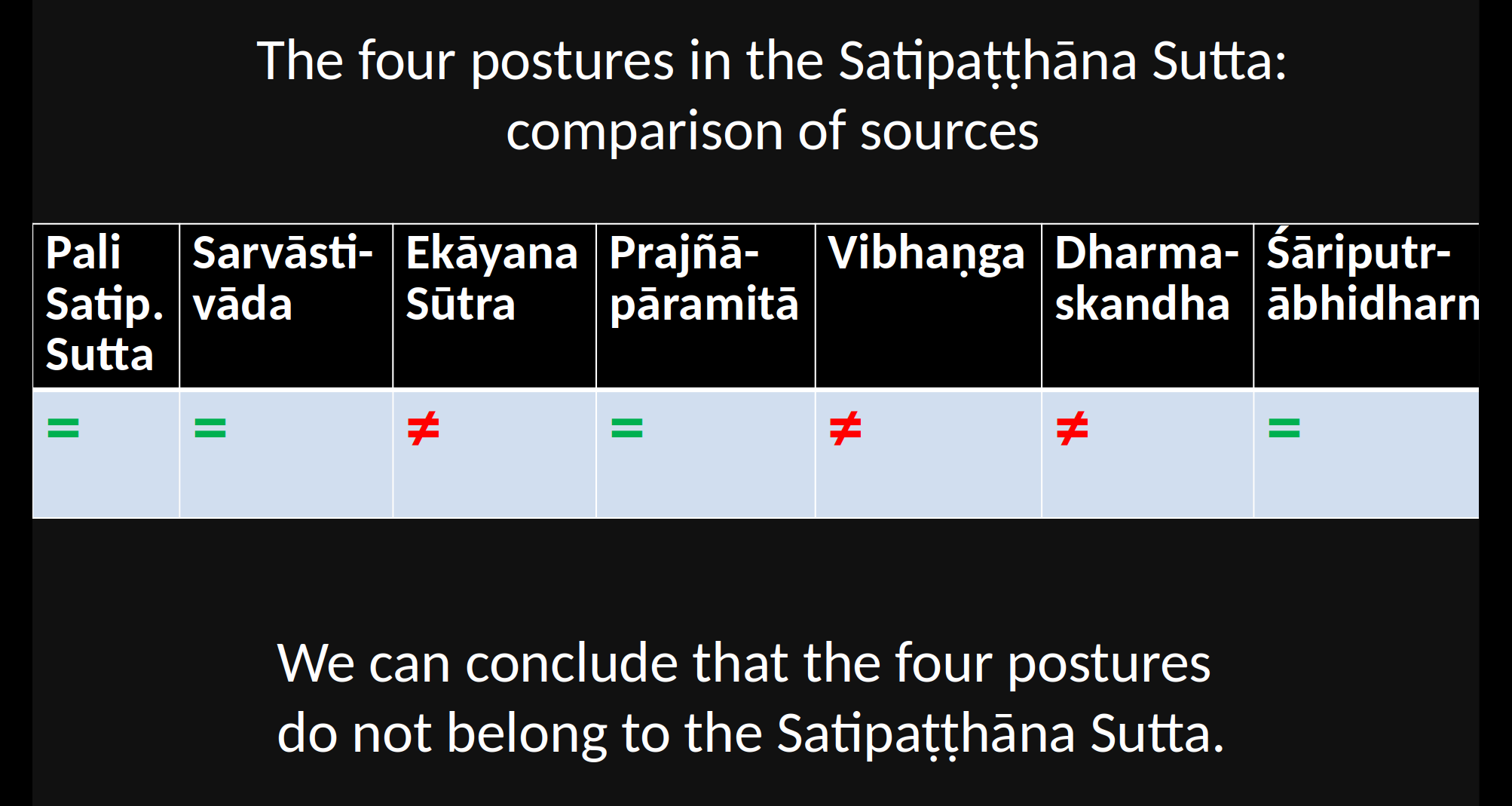

(6) Satipaṭṭhāna is to be practiced in everyday life

The Postures

“Furthermore, when you are walking you know: ‘I am walking.’ When standing … when sitting … when lying down you know: ‘I am lying down.’ Whatever posture your body is in, you know it.”

Full Awareness

“Furthermore, one acts with full awareness when going out and coming back; when looking ahead and aside; when bending and extending the limbs; when bearing the outer robe, bowl and robes; when eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting; when urinating and defecating; when walking, standing, sitting, sleeping, waking, speaking, and keeping silent.”

So where does full awareness belong? The suttas distinguish between mindfulness (sati) and full awareness (sampajaññā):

“Wise attention (yoniso manasikāra) > Full awareness > Sense restraint > Morality > Satipaṭṭhāna” (AN 10.61)

In the gradual training leading up to satipaṭṭhāna:

Morality > Contentment > Sense restraint > Full awareness > Seclusion > Meditation + abandoning the five hindrances = satipaṭṭhāna. (MN 27)

So full awareness (sampajaññā) comes before satipaṭṭhāna and is an aspect of right effort. The idea of practicing meditation, satipaṭṭhāna, in daily life has no basis in the suttas.

Meditation in daily life is based on the problematic idea that you become mindful by being mindful.

What is required in daily life is sufficient mindfulness to enable effective sense restraint.

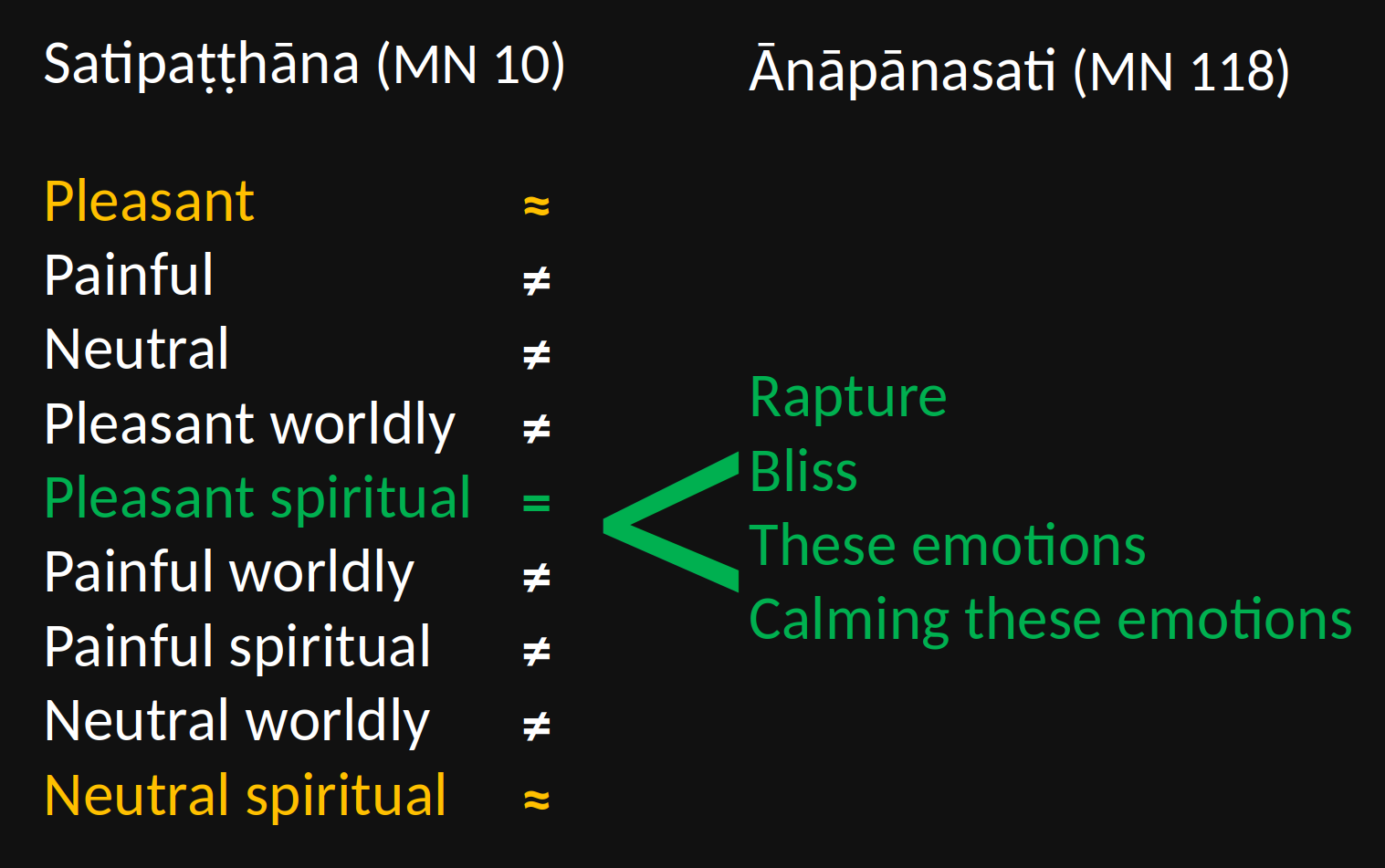

(7) Satipaṭṭhāna includes watching pain

Contemplating feelings in Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta:

“… When they feel a painful feeling, they know: ‘I feel a painful feeling.’ …

When they feel a worldly painful feeling, they know: ‘I feel a worldly painful feeling.’” (MN10)

Contemplating feelings in Ānāpānasati Sutta:

“They practice breathing in/out experiencing rapture. They practice breathing in/out experiencing bliss. They practice breathing in/out experiencing these emotions. They practice breathing in/out stilling these emotions.

Whenever one practices these things, at that time one meditates contemplating an aspect of feelings …” (MN 118)

It is clear from the Ānāpānasati Sutta that one does not need to contemplate painful feelings directly, see discussion on anupassanā. Instead they can be contemplated though their absence.

This is a much more powerful way of contemplating them because you see the three characteristics with full force.

Summary of myths/misconceptions

- Satipaṭṭhāna develops mindfulness

- You are either mindful or you are not

- Satipaṭṭhāna is “the one and only way”

- Satipaṭṭhāna is all about direct observation: anupassanā/vipassanā

- Breath meditation belongs to body contemplation

- Satipaṭṭhāna is to be practiced in everyday life

- Satipaṭṭhāna includes watching pain.

Overview of the Pali Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta

Introduction

- Contemplation of the body (kāyānupassī)

- Contemplation of feelings (vedanānupassī)

- Contemplation of mind (cittānupassī)

- Contemplation of mental qualities or principles (dhammānupassī)

Conclusion

Contemplation of body

- Mindfulness of breathing

- 4 postures

- Clear awareness

- 31 parts of the body

- 4 elements

- Charnel ground contemplations

Contemplation of the 31 parts of the body

“Again, a monastic reviews (paccavekkhati) their own body, up from the soles of the feet and down from the tips of the hairs, wrapped in skin and full of many kinds of filth (asuci):

‘In this body there is head hair, body hair, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, undigested food, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, snot, synovial fluid, urine.’It’s as if there were a bag with openings at both ends, filled with various kinds of grains, such as fine rice, wheat, mung beans, peas, sesame, and ordinary rice.

And someone with good eyesight were to open it and review the contents:

‘These grains are fine rice, these are wheat, these are mung beans, these are peas, these are sesame, and these are ordinary rice.’”

Why this contemplation? To overcome attachment to the body, the main obstacle to meditation. Can be done as stand-alone meditation or as a preliminary part of breath meditation. 31 or 32 parts of the body? Suttas vs. commentaries.

Contemplation of the 4 elements

“Again, a monastic examines their own body, whatever its placement or posture, according to the elements:

‘In this body there is the earth element, the water element, the fire element, and the air element.’

It’s as if a deft butcher or butcher’s apprentice were to kill a cow and sit down at the crossroads with the meat cut into portions.”“And what is the interior earth element?

Anything hard, solid, and appropriated that’s internal, pertaining to an individual.

This includes: head hair, body hair, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, undigested food, feces, or anything else hard, solid, and appropriated that’s internal, pertaining to an individual.The interior earth element and the exterior earth element are just the earth element.

This should be truly seen with right understanding like this: ‘This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self.’

When you truly see with right understanding, you grow disillusioned with the earth element, detaching the mind from the earth element.”

(MN 28)

Body contemplation summary

- Emphasis on letting go of the body

- This is a support for breath meditation

- The weaker the attachment to the body, the easier the breath meditation

- Eventually breath meditation takes over.

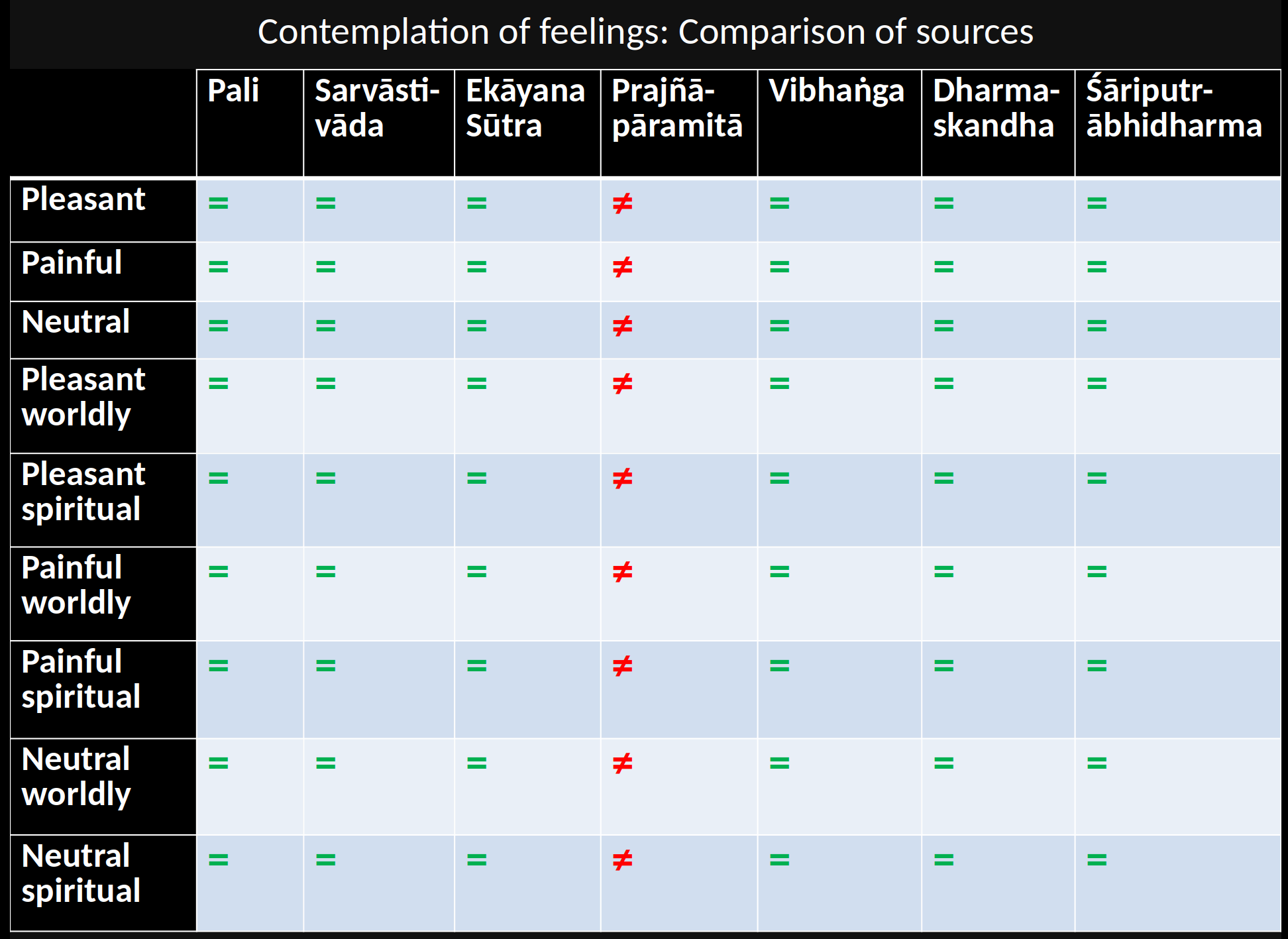

Contemplation of feelings

“When a monastic feels a pleasant feeling they know: ‘I feel a pleasant feeling.’ When they feel a painful feeling, they know: ‘I feel a painful feeling.’ When they feel a neutral feeling, they know: ‘I feel a neutral feeling.’

When they feel a worldly pleasant feeling, they know: ‘I feel a worldly pleasant feeling.’ When they feel a spiritual pleasant feeling, they know: ‘I feel a spiritual pleasant feeling.’

When they feel a worldly painful feeling, they know: ‘I feel a worldly painful feeling.’ When they feel a spiritual painful feeling, they know: ‘I feel a spiritual painful feeling.’

When they feel a worldly neutral feeling, they know: ‘I feel a worldly neutral feeling.’ When they feel a spiritual neutral feeling, they know: ‘I feel a spiritual neutral feeling.’” (MN 10)

Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta vs. Ānāpānasati Sutta: contemplation of feelings

“When they feel a spiritual pleasant feeling (nirāmisa sukha), they know: ‘I feel a spiritual pleasant feeling.’”

“It’s when a monastic, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unskillful qualities, enters and remains in the first absorption (jhāna) … in the second absorption.” (SN 36.31)

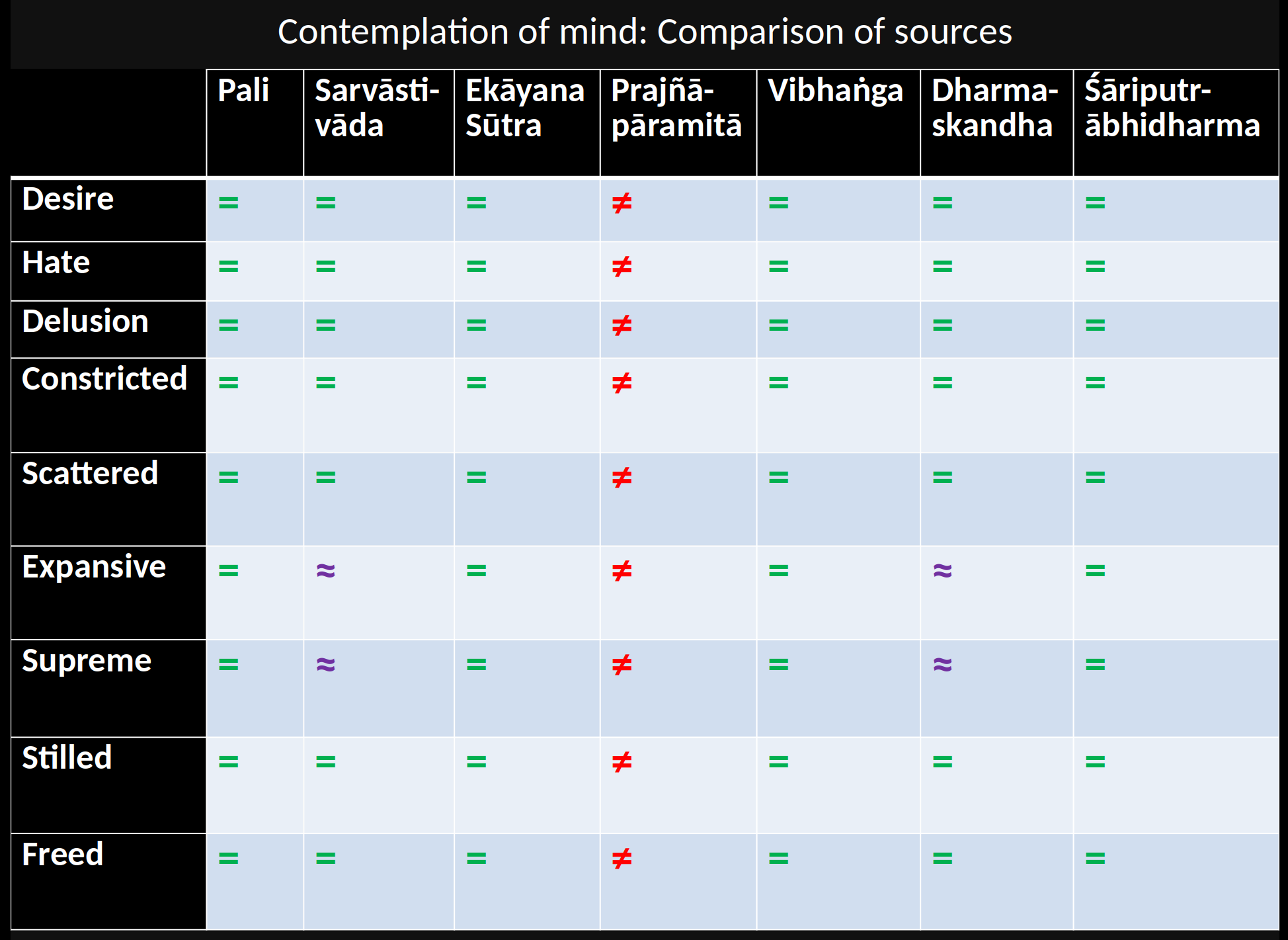

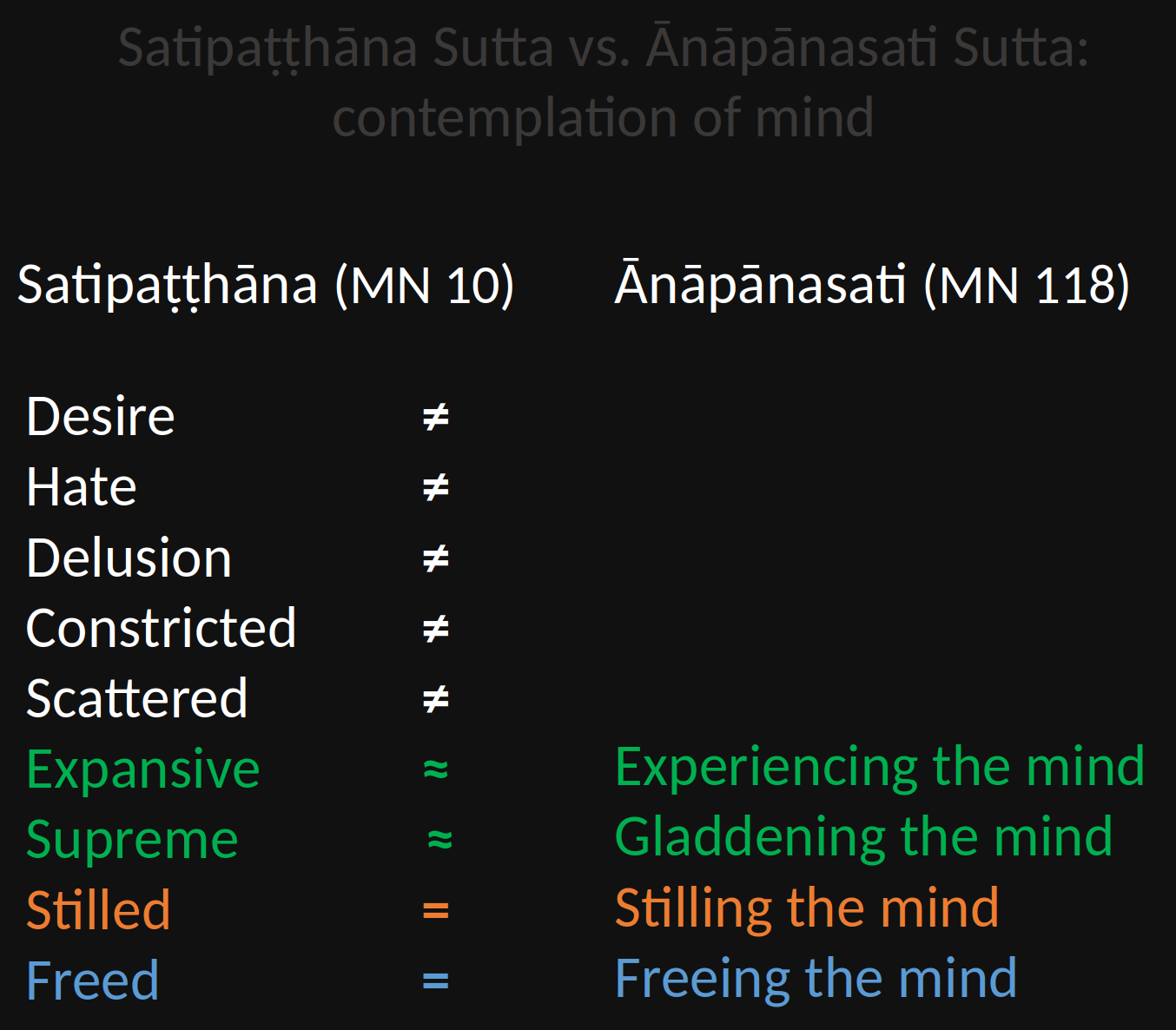

Contemplation of mind

“A monastic understands mind with desire as with desire, and mind without desire as without desire. They understand mind with hate as with hate, and mind without hate as without hate. They understand mind with delusion as with delusion, and mind without delusion as without delusion. They know constricted mind as constricted, and scattered mind as scattered.

They know expansive mind as expansive, and unexpansive mind as unexpansive. They know non-supreme mind as non-supreme, and supreme mind as supreme. They know a stilled mind as stilled, and an unstilled mind as unstilled. They know a freed mind as freed, and an unfreed mind as unfreed.” (MN 10)

Summary feelings and mind

- It is the positive feelings and mind states that really matter as direct experiences.

- The negative states can largely be understood through their absence.

- The only meditation found in the suttas that gives a framework for the contemplation feelings and mind states is the breath.

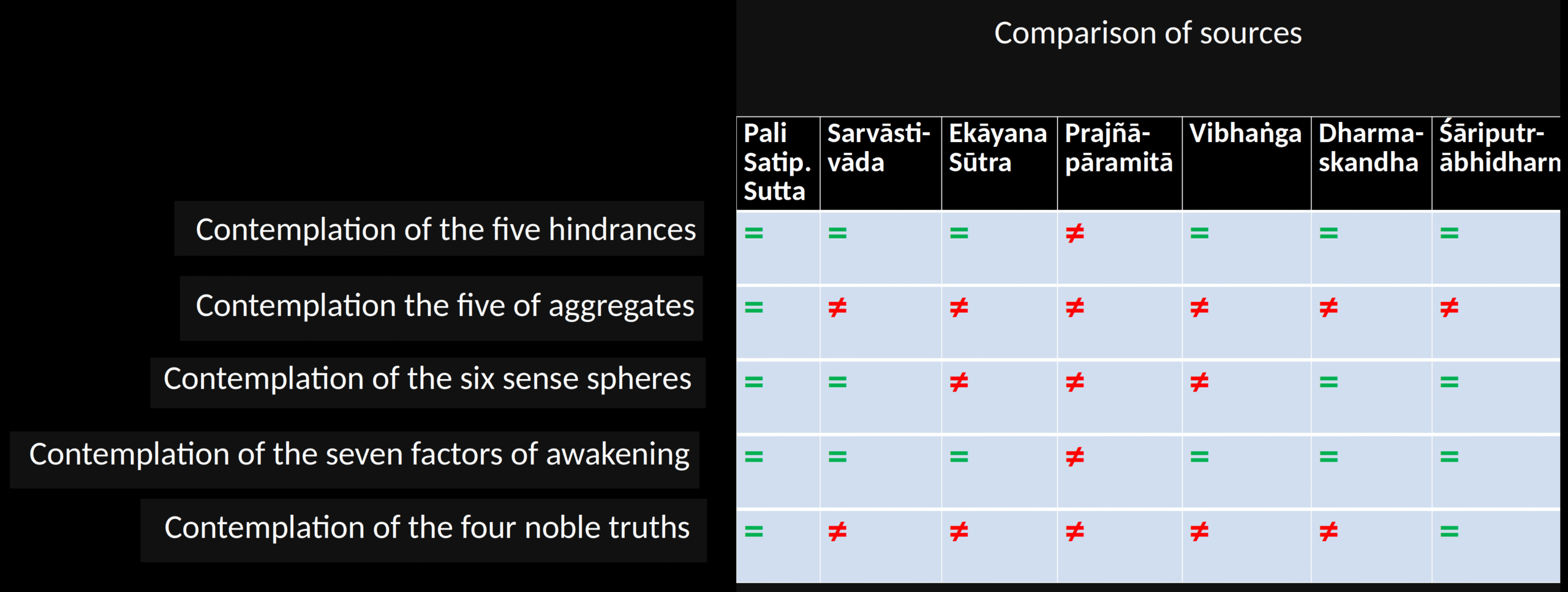

Contemplation of dhammas

- 5 hindrances (nīvaraṇa) (MN 10)

- 5 aggregates (khandha)

- 6 sense spheres (āyatana)

- 7 factors of awakening (sambhojaṅga)

- 4 noble truths (ariya sacca)

What is dhamma in this context? Two main possibilities:

- Aspect of experience (phenomenon)

- Law of nature (principle)

But all four satipaṭṭhānas are about aspects of experience. What distinguishes the fourth satipaṭṭhāna is its focus on causality.

“It’s when a monastic who has sensual desire in them understands: ‘I have sensual desire in me.’

When they haven’t sensual desire in them, they understand: ‘I haven’t sensual desire in me.’

They understand how sensual desire arises.

They understand how, when arisen, it’s given up.

And they understand how, once it’s given up, it doesn’t arise again in the future.”

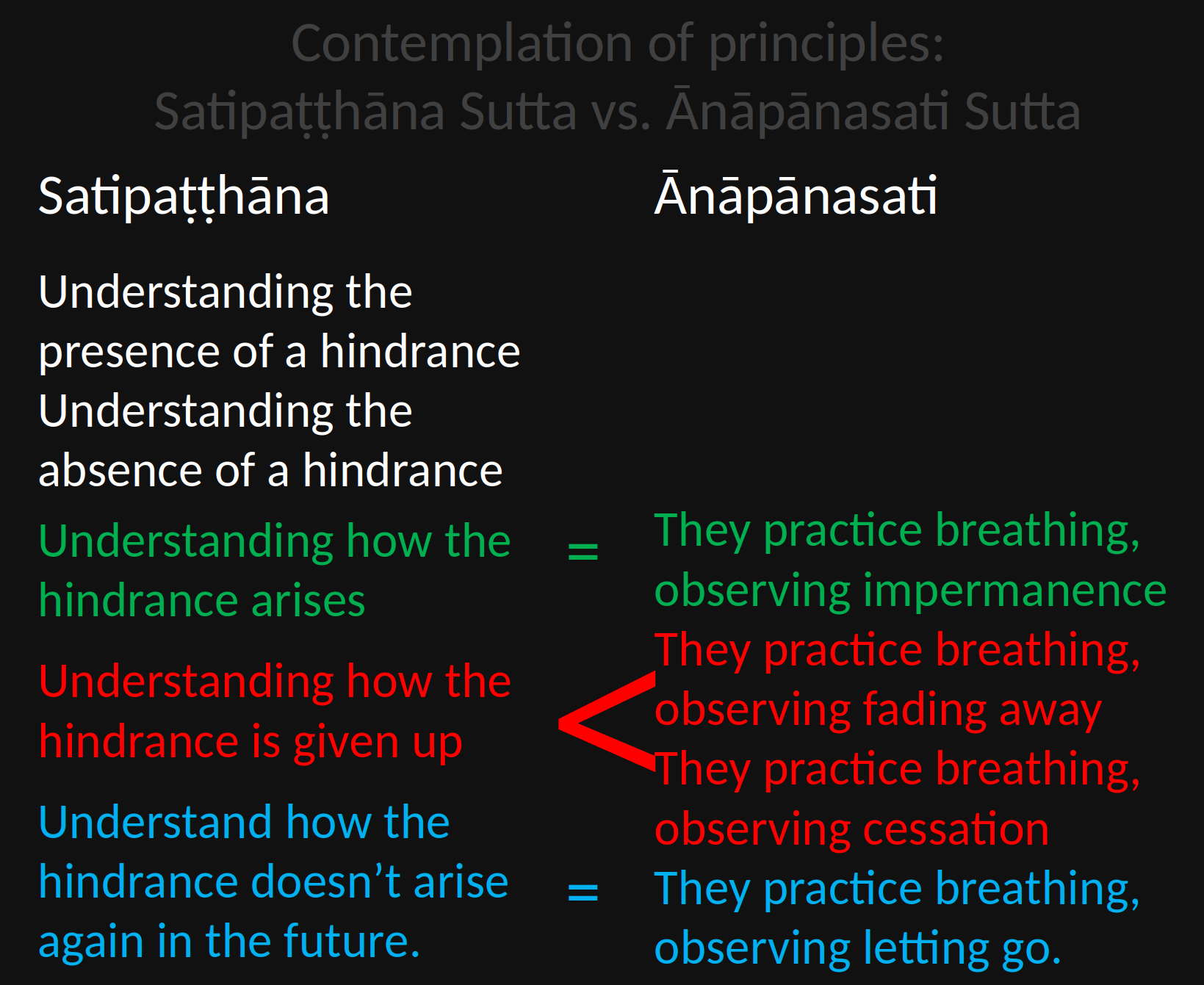

Contemplation of the five hindrances

“It’s when a monastic who has sensual desire in them understands: ‘I have sensual desire in me.’

When they don’t have sensual desire in them, they understand: ‘I don’t have sensual desire in me.’

They understand how sensual desire arises.

They understand how, when it’s arisen, it’s given up.

And they understand how, once it’s given up, it doesn’t arise again in the future.”

“It’s when a monastic who has anger … dullness and drowsiness … restlessness and remorse … doubt in them understands: ‘I have doubt in me.’

When they don’t have doubt in them, they understand: ‘I don’t have doubt in me.’

They understand how doubt arises.

They understand how, when it’s arisen, it’s given up.

And they understand how, once it’s given up, it doesn’t arise again in the future.”

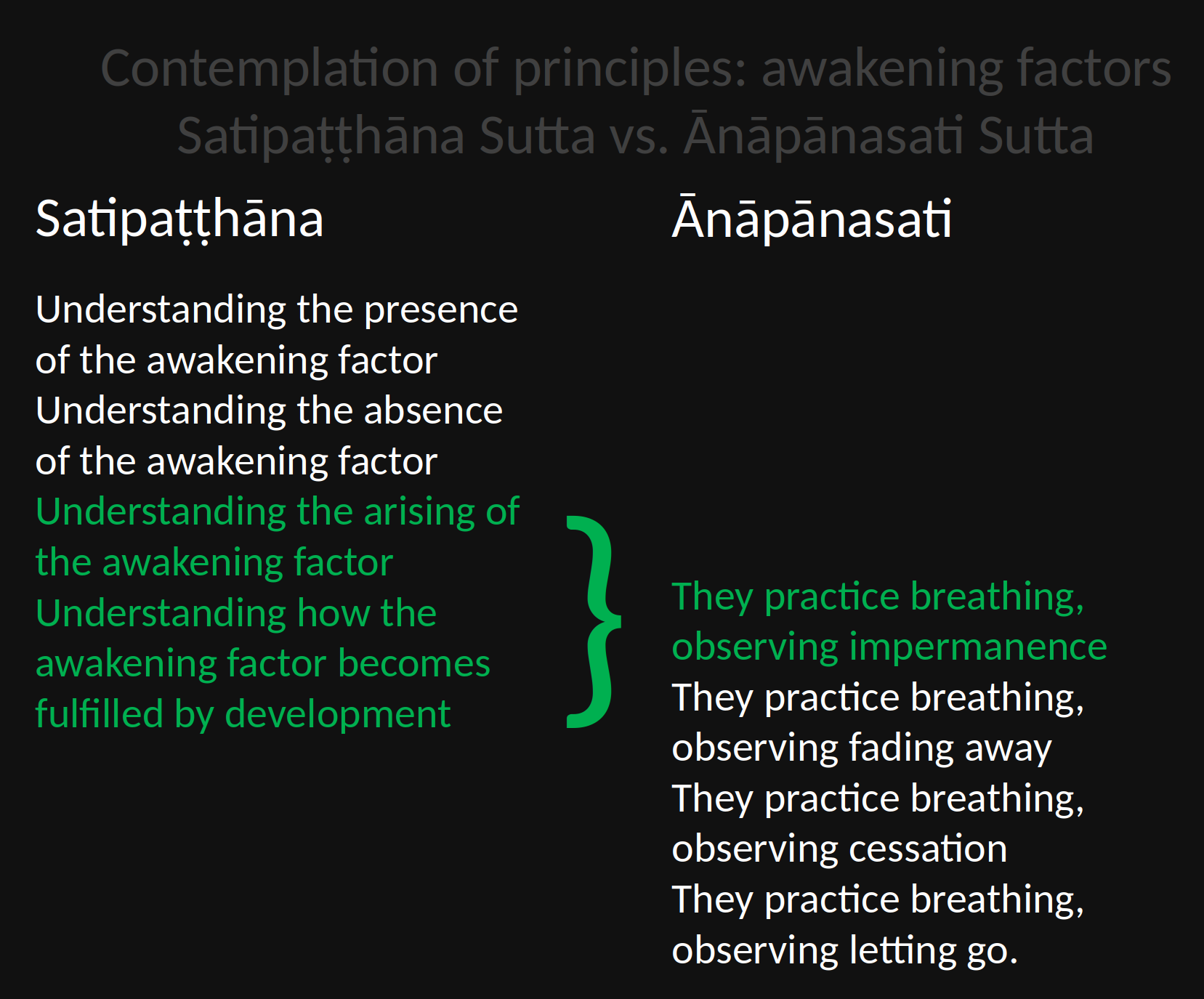

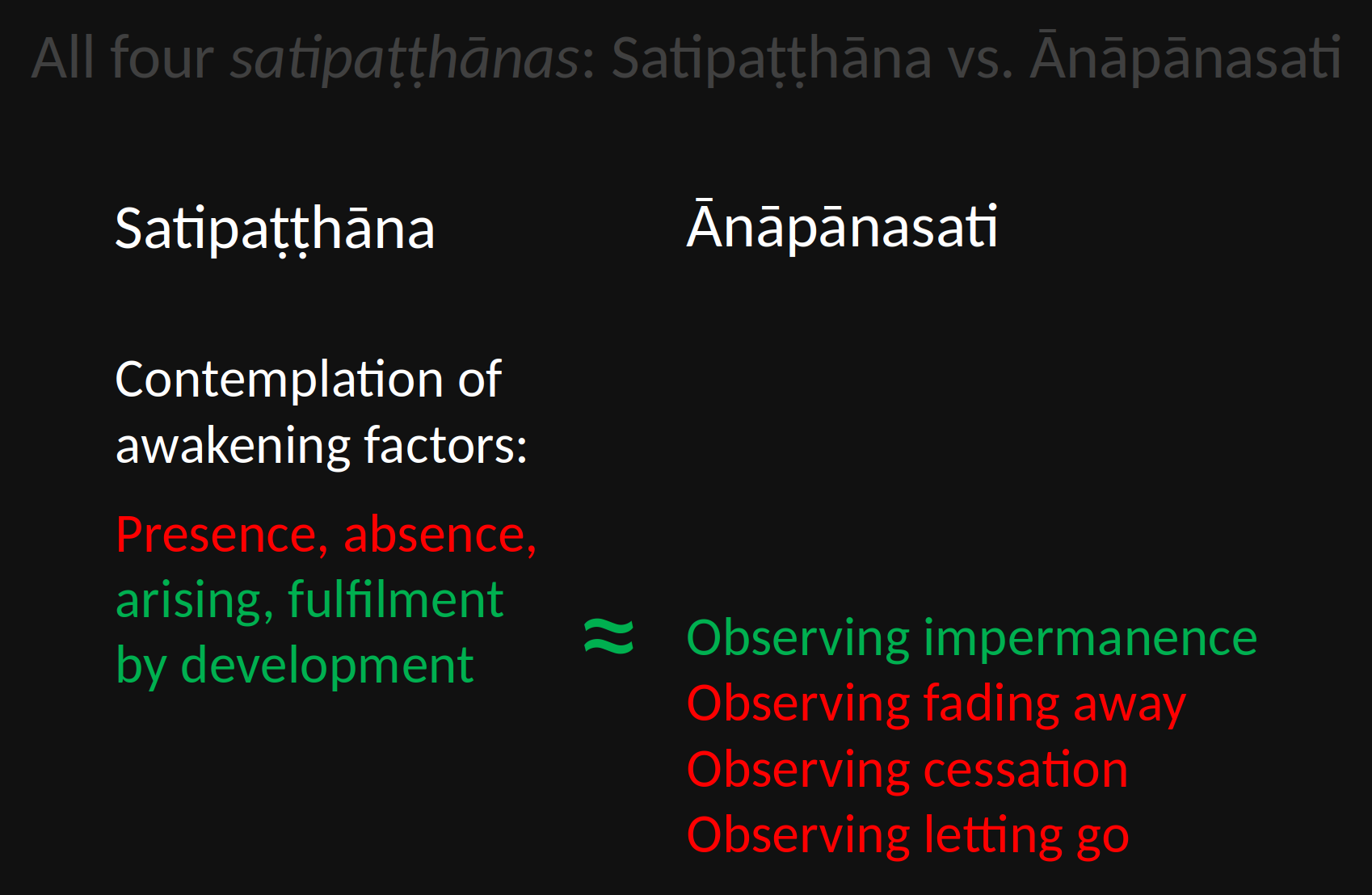

Contemplation of the seven factors of awakening

“It’s when a monastic who has the awakening factor of mindfulness in them understands: ‘I have the awakening factor of mindfulness in me.’

When they don’t have the awakening factor of mindfulness in them, they understand: ‘I don’t have the awakening factor of mindfulness in me.’

They understand how the awakening factor of mindfulness that has not arisen comes to arise;

And they understand how the awakening factor of mindfulness that has arisen becomes fulfilled by development.”“It’s when a monastic who has the awakening factor of investigation of principles … energy … rapture … tranquility … stillness … equanimity in them understands: ‘I have the awakening factor of mindfulness in me.’

When they don’t have the awakening factor of equanimity in them, they understand: ‘I don’t have the awakening factor of equanimity in me.’

They understand how the awakening factor of equanimity that has not arisen comes to arise;

And they understand how the awakening factor of equanimity that has arisen becomes fulfilled by development.”

5 hindrances vs. 7 factors of awakening

“These five hindrances are destroyers of sight, vision, and knowledge. They block wisdom, they’re on the side of anguish, and they don’t lead to Nibbāna. What five? Sensual desire, ill will, dullness and drowsiness, restlessness and remorse, and doubt.

These seven awakening factors are creators of vision and knowledge. They grow wisdom, they’re on the side of solace, and they lead to Nibbāna. What seven? The awakening factors of mindfulness, investigation of principles, energy, rapture, tranquility, stillness, and equanimity.” (SN 46.37)

“Monastics, please give up the five hindrances (nīvaraṇa)—corruptions of the heart that weaken wisdom—and truly develop the seven awakening factors (bojjhaṅga).” (SN 46.52)

“All the perfected ones, fully awakened Buddhas—past, future, or present—gave up the five hindrances, corruptions of the heart that weaken wisdom. Then with their mind firmly established in the four kinds of mindfulness meditation, they correctly develop the seven awakening factors. And they wake up to the supreme perfect awakening.” (SN47.12)

Summary Satipaṭṭhāna

- Gradual development of satipaṭṭhāna

- This is best seen through breath meditation

- Breath meditation is what holds it all together and gives it a firm anchor

- The content of the suttas is diminished because of misconceptions, making satipaṭṭhāna much less profound than it actually is. Then samādhi and everything else are also diminished, reducing the Dhamma to a lesser teaching, not leading to liberation.

Summary of entire course

- To understand satipaṭṭhāna you need to read the suttas widely

- Morality and right view are what enable satipaṭṭhāna

- Satipaṭṭhāna is about meditation, which requires mindfulness

- Satipaṭṭhāna develops samatha and vipassanā, leading to samādhi

- Breath meditation is the main sutta approach to all satipaṭṭhāna practice

- Satipaṭṭhāna + samādhi brings about awakening.

Del gjerne denne siden med en venn: